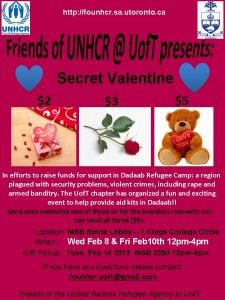

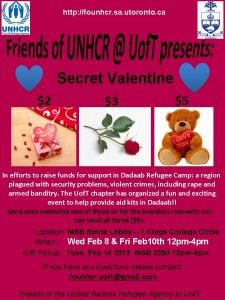

Help Us Aid Refugees in Dadaab Refugee Camp by Buying Your Valentine Gifts!

Last year, more than 160,000 Somalis fled to Kenya to escape draught, famine and fighting in their homeland and a further 98,000 are sheltering in Ethiopia.

Many who set off for neighbouring countries do not survive the perilous journey. Mothers have been forced to watch, powerless, as their children die. Those that do make it to refugee camps are arriving in a terrible condition.

They need urgent medical assistance and nutritional support. They also need clean drinking water and shelter to protect them from the harsh climate.

UNHCR can give them this. We provide shelter, food, water, medical care and other basic necessities for refugee children and their families.

Money raised through this fundraiser will be used for:

$50: provides the five week supply of ready-to-use therapeutic food needed to bring back to health a severely malnourished child.

$100: survival kits – each has a blanket, mattress, kitchen set, stove and soap

$450: all-weather tent to shelter a refugee family

$5,500: nutrition survey kit, includes weighing scales (x5), height measuring board, haemocue machine and accessories (microcuvettes, lancet, etc.), and mid upper arm circumference tape

Here is more information by Debi Goodwin from the Globe and Mail about Dadaab:

Little has galvanized the world’s attention to the largest refugee camp in the world: Dadaab, a place described by UNHCR’s head Antonio Guterres as the “most difficult camp situation in

the world,” a situation Médecins Sans Frontières called a humanitarian emergency. Despite the warnings, Dadaab remains underfunded and overcrowded. Attempts at publicity, like the visit two years ago by celebrity UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador, Angelina Jolie, have done little to change the lives of those stuck there.

Recently, the Danish Refugee Council, perhaps out of frustration, devised a bolder strategy. It created a game with the working title of The Worst Vacation Ever, and posted on Facebook as “The City That Shouldn’t Exist.” Players were asked to save the lives of 100,000 hungry, thirsty refugees headed to the world’s largest camp, with the chance to win a trip for two to Dadaab. The agency was attempting to reach out to young people in a medium they understood, but had to suspend the game after over criticism of insensitivity.

If the three camps that make up Dadaab were a city, it would be Kenya’s fourth largest, but one at the fringes of its citizens’ consciousness. When the Kenyan government realized how many Somali refugees were flooding into the country after the Somali civil war in 1991, they pushed thousands of refugees into the camps in the remote northeastern region far from the centre of power in Nairobi, far from opportunity. The camps should have provided temporary shelter for 90,000 people, but as the war and ensuing anarchy continued in Somalia they became home to more than 300,000 people. MSF predicts there will be 450,000 residents by the end of the year.

There are young adults who have spent their whole lives in the camps. And they live with restrictions unimaginable to few outside of prison. There is little possibility of movement beyond the camp. There is no chance of getting a job or of integrating into “the real Kenya.” The Kenyan government offers none of the rights described in the UN’s 1951 refugee convention. And the Western world does little to protest this treatment.

Life in the hot, arid camps is hard. There is rarely enough food, water or safety. Yet each month about 5,000 people cross the nearby, closed border with Somalia. In 2008, UNHCR declared the camps full. That summer I talked to new arrivals who had walked for days across the desert to get to Dadaab, only to find there was nowhere for them to live. They slept under the few acacia trees large enough to provide shade and lined up for ration cards for food. When Ms. Jolie visited the camps in 2009, she commented: “If this is the better solution, what must it be like in Somalia?”

Just as no one has found a solution for peace in Somalia, no one has envisioned lasting solutions to the crisis of Dadaab. A handful of countries, including Canada, resettle families. Canadian university students sponsor a dozen or so single young people through World University Service of Canada. UNHCR attempted to expand the camps until talks with local leaders broke down. Even if more space could have been found, the solution would have been temporary and done nothing to address the underlying horror of people being warehoused because no one knows what to do.

UNHCR came into existence after the Second World War with the aim of protecting the rights of displaced people. When refugees were still living in camps well into the 1950s, then High Commissioner for Refugees, Gerrit Jan van Heuven Goedhart, called those camps “black spots on the map of Europe” and warned residents could become “easy prey for political adventurers.” Today, the majority of refugees under UNHCR’s care remain in camps, their lives on hold for the unforeseeable future – in camps, like Dadaab, that we must come to accept as black spots on the globe before lasting solutions can be found.